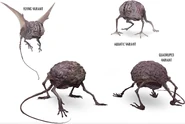

Intellect devourers were psionic aberrations that took the form of walking brains. They were servants of the mind flayers and were one of the most dreaded threats of the Underdark, with their power to consume intelligence and possess host bodies.[7][6][5][4][2][3] They were also known as brain-dogs[1] and rochnon (pronounced: /ˈrɒknɒn/ ROCK-non[12]).[12]

Description[]

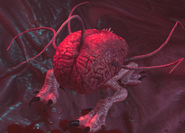

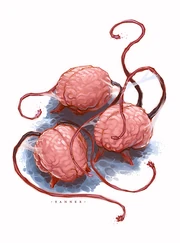

They looked like little more than disembodied large humanoid brains that could walk on a set of four bestial double-jointed bony legs with feet bearing three stubby talons.[7][6][5][4][3] Though their size was variable thanks to their psionic compression power, they ranged in size from 6 inches (15 centimeters) long,[6] to about as big as dogs. Despite their appearance, they could move and attack with shocking speed.[5][4] Their brain matter was protected under a crusty coating[7][5][3] or a glistening, clear membrane.[4] They made warbling sounds.[12]

Behavior[]

The intellect devourer had a kind of split personality, enabling it to perform different actions simultaneously.[6][5] They were only active when it was dark.[5]

Abilities[]

They were capable of magically consuming a humanoid creature's mind and memories from a distance of up to 10 feet (3 meters), provided that creature had a brain and succumbed to its psychic assault. If so, the victim's mentality was deteriorated. In the worst case, the victim's intellectual capacity was completely erased, leaving them dazed or stunned and ultimately incapacitated.[2][3] Psionic intellect devourers instead absorbed mental energy as with psychic drain or consumed the victim's confidence, as with the ego whip power.[7][6][5][4]

If the intellect devourer approached a vulnerable victim (whether incapacitated or already devoured) within 5 feet (1.5 meters), it could then battle the brain's remaining defenses; a protection from evil spell prevented this and repelled them.[7][6][5][4][3] If successful, it magically or psionically consumed the physical brain, then teleported inside the empty skull to replace the brain, whereupon it could use the body as a host,[6][5][4][3] as with a domination power.[6][5] Naturally, this killed the victim. A fresh corpse could also be used as a host, but not undead and other kinds of creatures not especially hampered by the loss of a brain.[5][4] Any difference in size was taken care of by their compression power.[6][5][4]

Once in control of its host, an intellect devourer had full control of the body, which was more or less as strong and capable as it was normally, while the devourer retained its own mental abilities.[4][2][3] Moreover, the intellect devourer possessed partial or complete knowledge of everything the victim had known, including all languages[4][3] surface knowledge of identity and personality but no specific memories or information,[4][3] or even all their knowledge and even their spells.[3] However, it would likely lose this knowledge once it vacated the host body.[4] When controlling a body, the intellect devourer wasn't always able to perfectly mimic the movements of certain races, such as humans.[13]

I'm in your head.

Safely ensconced inside the host body, it could not be easily attacked or targeted itself. It could only be removed by a protection from evil and good. However, this process killed the host body unless the original brain was somehow restored within a few seconds. Alternatively, a wish spell could restore the host's brain, forcing the intellect devourer out. If the host body was killed or the intellect devourer was forced to leave by some means, then it teleported to a place 5 feet (1.5 meters) away.[3] An intellect devourer could also leave willingly, by exploding out of the skull.[4] Otherwise, if not exposed, it could apparently control the body indefinitely,[14] though some accounts suggested seven days before needing to refresh.[4][note 1]

To aid in hunting, an intellect devourer could detect the minds of sentient creatures up to a distance of 300 feet (91 meters), determining both presence and position. Walls and other barriers made no difference, but a mind blank spell rendered the mind effectively invisible.[3] Some could also detect psionics to 60 feet (18 meters).[6][5][4] Otherwise, having no eyes, an intellect devourer could not be blinded nor assailed by magical gazes, yet could, by nonvisual senses, effectively "see" with blindsight up to 60 feet (18 meters) and pinpoint all creatures in range.[4][2][3] Their awareness in fact extended onto the astral plane and the ethereal plane.[7]

They could communicate via telepathy to 60 feet (18 meters).[3] Otherwise, they could not speak, though they could understand a language, such as the Deep Speech used by mind flayers[3] any language of humans,[7] or Common. If in a host, however, they could use the body to speak.[4]

But the intellect devourer's most vicious mental attack is disinterest.

Some intellect devourers were capable of various other psionic powers, such as the basic contact and mindlink for initiating psionics; ESP to read minds; telempathic projection to project their own feelings;[6][5] chameleon power[6][5] or cloud mind to creep about unnoticed;[4] expansion and compression or reduction to shrink and conceal themselves;[6][5][4] empty mind,[4] mind blank, or thought shield[7][6] to fortify their own mental defenses; ectoplasmic form[6][5] or intellect fortress to shield their bodies;[6][4] aversion to repel foes;[6] id insinuation to confuse a few opponents,[7][6][4] chemical simulation to produce an acid;[5] body equilibrium to balance on any surface;[6][5] body adjustment to heal themselves; painful strike to enhance their claws;[4] and even astral projection.[6][5] They were highly shielded against psionics themselves.[6][4][note 2]

Despite their exposed brains, an intellect devourer was protected by a crusty covering[3] or clear membrane[4] and was resistant to physical harm.[3] They sometimes required a highly enchanted or adamantine weapon to effectively harm them and were immune to fire and highly resistant to electricity,[7][6][5][4] thanks to a unique form of psionic energy containment.[6][5]

They were naturally skilled in stealth,[7][4] deception, and hearing.[4]

They fought using their taloned feet.[7][6][4][2][3]

Tactics[]

"Go for the brains, Boo!" An intellect devourer pouncing on a githyanki, sworn enemy of illithid-kind.

Intellect devourers would wander through tunnels and caves on the hunt for sentient prey.[2][7] They were particularly alerted to the presence of psionic energy and creatures that possessed psionic ability;[7][6] the greater the target's intelligence, the more like they were to attack.[12][15] When they sensed prey, they stalked them or else concealed themselves, using their powers to aid them, then waited for their chosen victim to be alone. They would then attack with all their psychic powers,[7][6][5][4] before charging in and pouncing to finish the target off with their claws.[7][6][5][4][2][3] Thanks to their split personality, they had no issue with using claws and psionics simultaneously.[6]

Afterward, the intellect devourer could seize the victim as a host and thereby infiltrate areas that offered it even more sentient minds to prey upon.[7][6][5][4]

If they found themselves seriously threatened, they would retreat for their own safety. They could also be driven off with a bright light, including from a natural fire.[7][6]

Ecology[]

The intellect devourer, as the name suggested, consumed the intelligence of sentient creatures,[3] which could be in death or by subtle harvesting.[7] Nevertheless, they would feed until the victim was no more than a mindless husk.[2]

The intellect devourers' means of reproduction was understandably a mystery to most surface dwellers.[6] In fact, illithids bred intellect devourers by subjecting the brain of one of their thralls to a ritual in which the brain sprouted legs and became an independent, intelligent predator.[3] The process involved immersing the brain in a 'spawning pool' containing a glowing green brine that would magically transmute the brain into a devourer over a few days. The process could be unreliable; the mind flayer Nihiloor saw nine in ten of these brains rot and die instead.[17] The illithids created intellect devourers from the brains they elected not to eat themselves.[18] However, it was also reported that intellect devourers arose from the remaining brains of creatures slain by other intellect devourers. In this version, they seemed to be psychic parasites spawned by the insanity of the Far Realm and they still bore its taint.[2]

Cute little baby brains.

Either way, the newly created aberration began its existence in a larval form called an ustilagor.[6][5][11][2] Mature intellect devourers did not protect or aid them, and would even eat them.[6][5] These ustilagor lived like rats and other vermin, only scavenging off the mental energies of bigger creatures[2] and were farmed as a delicacy by illithids unless raised to maturity.[6][11] An ustilagor that consumed the brain of a psionic creature would become an adult.[6]

A mature intellect devourer, also called an intellect predator to distinguish it from the other stages of life, operated similarly to a wolf. They hunted in packs[2] known as 'pods' of up to four specimens,[4] but they could also be found alone[7][6][5][4] or in pairs.[7][6][5][4] However, it was unusual for them to operate together like this.[5]

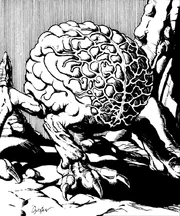

Rarely, an intellect predator that lived a long time and grown massive on consumed intelligence underwent a second metamorphosis, becoming what was known as an intellect glutton or brain collector. Too big to take a host body, these were powerful creatures in their own right.[2][note 3]

Some sages wondered if kalmari were related somehow to intellect devourers.[19]

Habitats[]

These predators were found prowling the underground and in the Underdark, independently and in service to the illithids.[7][6][5][4][2][3] They were usually found near other aberrant beings, particularly the mind flayers.[2] However, they might also be found in their own dark bleak dens in the wilds.[7][6][5]

Naturally, intellect devourers might be found hunting in Undermountain, including in the areas of Maddgoth's Castle.[20]

Intellect devourers could also be encountered in the astral plane and ethereal plane.[7][8][9][10] In the Abyss, they could be found in Shedaklah, the Slime Pits, the 222nd layer of the Abyss.[21]

Usage[]

The illithid Nihiloor playing with its pets.

Illithids used their intellect devourers for hunting. Normally, they had them possess and puppeteer the bodies of their victims and then use them to lure other creatures into the illithids' hunting grounds, so the mind flayers could consume their brains themselves or dominate them as new thralls.[3] Otherwise, they kept them as guard beasts[6][5][2] and even as pets, while an intellect glutton might be ridden as a mount.[2]

More generally, other intelligent creatures who dared to use intellect devourers would set them to work as guardians[2] or as predators for some purpose. By taking a host body and posting as their last victim, they made for excellent spies.[4]

The body parts of intellect devourers could be utilized as material components in potions and magic items associated with mind control and ESP.[6] Dried blood of intellect devourer (or brain mole, or formian) was a possible component in a sending.[22] A whole body was needed for a certain potion that bolstered one's psionics attack and defense powers.[23] Most notably, the brain of an intellect devourer was a key reagent in the cure for the disease known as the Wailing Death.[13] Intellect devourer cerebellum could be distilled into a suspension of cerebrospinal fluid, that, in turn, could be combined with certain alchemical sublimates to produce an elixir of psychic resistance.[24]

History[]

According to one ancient rumor, which was heard by the phaerimm some time before −339 DR, early humans banished to the Underdark, starving and desperate and eating anything they could find, went so far as to consume intellect devourers. Supposedly they were mutated, becoming the first illithids. It was further speculated this meant an illithid could be turned back into a human. While unlikely, it was enough for the phaerimm to distrust their mind flayer allies at the time.[25]

When the Wailing Death struck Neverwinter in the Year of Wild Magic, 1372 DR, Lord Nasher Alagondar enlisted Khelben "Blackstaff" Arunsun of Waterdeep to develop a magical cure. Khelben managed to do so, and sent four key ingredients, in the form of live beings—an intellect devourer, a cockatrice, a dryad, and a yuan-ti—to Neverwinter. These were kept at the Neverwinter Academy, but an attack by the Cult of the Eye allowed them to escape and scatter across the city. The intellect devourer took Captain Alaefin, Head Gaoler of Neverwinter's Prison, and let all the prisoners loose into the Peninsula District. The Hero of Neverwinter broke into the prison, slew the devourer-possessed gaoler, and carried its brain back to Lady Aribeth de Tylmarande.[13]

Brains versus brawn.

In the early 1400s DR, the elder brain Zuphelithid and its mind flayers commanded a half-dozen intellect devourers when they invaded parts of Dolblunde and enthralled the local deep gnomes. Fortunately, the paladin Xenk Yendar made mincemeat of the walking brains when he first confronted the greater elder brain.[26]

In the Year of Three Ships Sailing, 1492 DR, the mind flayer Nihiloor of the Xanathar's Thieves' Guild used intellect devourers to replace and control important people across Waterdeep.[27] It bred these in a spawning pool in Xanathar's Lair, where it also implanted them in captive hosts.[17] It let them roam Waterdeep's sewers to hunt, take hosts, infiltrate the city and send back what it learned, or else had them infiltrate specific targets in the City Watch or City Guard, or kidnap people for ransom or enthralling.[28] Its intellect devourers were inside four members of the Dungsweepers' Guild, for use as spies and thugs against threats to the guild,[29] and the Force Grey member Meloon Wardragon, who battled Zhentarim and steered adventurers away from Undermountain and against guild enemies.[14] Other intellect devourers aided in a plot to seize the Stone of Golorr.[30] The scheme was possibly uncovered by Force Grey, which would sent adventurers to investigate Meloon and to deal with Nihiloor and its pet intellect devourers at its guild hideout in Waterdeep.[27][31]

In any case, thugs and bugbears hosting devourers serving the Xanathar Thieves' Guild were found operating on the Dungeon Level and Arcane Chambers of Undermountain the following year to guard the way to their base, making for impossible-to-surprise sentries.[32] Meanwhile, several goblins and bugbears in the court of the hobgoblin warlord Azrok in Stromkuhldur on the Sargauth Level hosted the devourers; these were commanded by Ulquess, an illithid ambassador of Skullport also serving the Xanathar Thieves' Guild. They spied and spread (correct) rumors about Azrok's blindness and worked to take over the Legion of Azrok.[1]

Later, in the late 1490s DR,[note 4] Xenk Yendar returned to Dolblunde, leading the thieves Edgin Darvis, Holga Kilgore, Simon Aumar, and Doric on a mission to retrieve the helmet of disjunction that he'd left there almost a century before. On the way, they passed a trio of intellect devourers on patrol. He warned them of their powers and predilection for intellect, and urged them to keep quiet and out of the way. However, the three aberrations just walked on by.[12][15]

Notable Intellect Devourers & Hosts[]

Friends, family, coworkers—do you know someone who could be operating without a brain?

- Meloon Wardragon, a mercenary and Force Grey member in Waterdeep hosting an intellect devourer.[14]

- Ahpok, a grimlock host in the Seadeeps of Undermountain used by local illithids to lure grimlock victims and monitor their prisoners.[33]

- Us, an intellect devourer that was created from a high elf named Myrnath. Us could have had escaped the nautiloid of its birth with the aid of one of the True Souls in the Year of Three Ships Sailing, 1492 DR.[24]

Appendix[]

Notes[]

- ↑ Only the 3rd-edition intellect devourer has a time limit, arising from the mechanical duration of the psionic powers used to replicate its abilities. However, there seems nothing to stop it reusing its powers and repossessing the body. In other editions, this ability seems indefinite, with characters like Meloon Wardragon being hosts for at least a few months.

- ↑ Some psionic powers assigned to intellect devourers in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd editions seem intended to replicate abilities that would be handled with specific mechanics in prior and later editions. These have been linked to these abilities in the above paragraphs, while remaining powers are summarized here. It should be noted the psionics-using intellect devourer in Expanded Psionics Handbook is not intended as a variant like other psionic versions of creatures in that book are.

- ↑ Unique to 4th edition, the intellect glutton is not known to exist in the Forgotten Realms but is included here for completeness.

- ↑ The Honor Among Thieves movie and its tie-ins are as yet undated. As discussed here, from the condition of Castle Never and Dagult Neverember's reign, this wiki estimates a date of the late 1490s DR for the main events of the movie. Prequels and flashback scenes are set up to 11 years before this.

Appearances[]

Adventures

Novels & Short Stories

Film & Television

Comics

Video Games

Board Games

Card Games

Miniatures

Organized Play & Licensed Adventures

Background[]

The intellect devourer first appeared in the Monster Manual 1st edition, in 1977.

It was presumably planned for the Monster Manual 3rd edition in 2000, with concept art prepared by Sam Wood, seen below. This was a new design giving the intellect devourer an actual body, not merely a brain with legs. However, it would go unused, with the intellect devourer not appearing until the Psionics Handbook the following year with a more traditional design. Nevertheless, Wood's design was used in Neverwinter Nights, released the following year. The game includes variants: skeletal intellect devourers and battle intellect devourers.

External Links[]

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the following links do not necessarily represent the views of the editors of this wiki, nor does any lore presented necessarily adhere to established canon.

Intellect devourer article at the Eberron Wiki, a wiki for the Eberron campaign setting.

Intellect devourer article at the Eberron Wiki, a wiki for the Eberron campaign setting. Intellect Devourer article at the Baldur's Gate 3 Community Wiki, a community wiki for Baldur's Gate 3.

Intellect Devourer article at the Baldur's Gate 3 Community Wiki, a community wiki for Baldur's Gate 3.

Further Reading[]

- Clifford Horowitz (January 2003). “Silicon Sorcery: The Lost Horrors of Neverwinter Nights”. In Jesse Decker ed. Dragon #303 (Paizo Publishing, LLC), pp. 80–86.

Gallery[]

References[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Christopher Perkins (November 2018). Waterdeep: Dungeon of the Mad Mage. Edited by Jeremy Crawford. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 44, 56–58. ISBN 978-0-7869-6626-4.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 Mike Mearls, Greg Bilsland, Robert J. Schwalb (June 2010). Monster Manual 3 4th edition. Edited by Greg Bilsland, et al. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 118. ISBN 978-0-7869-5490-2.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 3.26 3.27 3.28 3.29 3.30 3.31 Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford, Christopher Perkins (2014-09-30). Monster Manual 5th edition. Edited by Scott Fitzgerald Gray. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 191. ISBN 978-0786965614.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 4.28 4.29 4.30 4.31 4.32 4.33 4.34 4.35 4.36 4.37 4.38 4.39 4.40 4.41 4.42 4.43 4.44 4.45 Bruce R. Cordell (April 2004). Expanded Psionics Handbook. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 202–203. ISBN 0-7869-3301-1.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 5.23 5.24 5.25 5.26 5.27 5.28 5.29 5.30 5.31 5.32 5.33 5.34 5.35 5.36 5.37 5.38 Steve Winter (1991). The Complete Psionics Handbook. (TSR, Inc.), p. 117. ISBN 1-56076-054-0.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 6.24 6.25 6.26 6.27 6.28 6.29 6.30 6.31 6.32 6.33 6.34 6.35 6.36 6.37 6.38 6.39 6.40 6.41 6.42 6.43 6.44 6.45 Doug Stewart (June 1993). Monstrous Manual. (TSR, Inc), p. 207. ISBN 1-5607-6619-0.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 7.22 7.23 7.24 7.25 7.26 7.27 7.28 7.29 7.30 Gary Gygax (December 1977). Monster Manual, 1st edition. (TSR, Inc), p. 54. ISBN 0-935696-00-8.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Gary Gygax (1979). Dungeon Masters Guide 1st edition. (TSR, Inc.), p. 181. ISBN 0-9356-9602-4.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 James Ward, Robert J. Kuntz (August 1980). Deities & Demigods. Edited by Lawrence Schick. (TSR, Inc.), pp. 132, 133. ISBN 0-935696-22-9.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Don Turnbull (1981). Fiend Folio. (TSR Hobbies), p. 119. ISBN 0-9356-9621-0.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Kevin Baase, Eric Jansing, Oliver Frank, and Bill Halliar (November 2005). “Monsters of the Mind – Minions of the Mindflayers”. In Erik Mona ed. Dragon #337 (Paizo Publishing), pp. 34–35.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Jonathan Goldstein, John Francis Daley (2023). Honor Among Thieves. (Paramount Pictures).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 BioWare (June 2002). Designed by Brent Knowles, James Ohlen. Neverwinter Nights. Atari.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Christopher Perkins, James Haeck, James Introcaso, Adam Lee, Matthew Sernett (September 2018). Waterdeep: Dragon Heist. Edited by Jeremy Crawford. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 20, 210. ISBN 978-0-7869-6625-7.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 David Lewman (February 28, 2023). Honor Among Thieves: The Junior Novelization. (Random House Worlds), chap. 18, pp. 122–123. ISBN 0593647955.

- ↑ Jeff Grubb, Kate Novak (October 1988). Azure Bonds. (TSR, Inc.), chap. 14, p. 165. ISBN 0-88038-612-6.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Christopher Perkins, James Haeck, James Introcaso, Adam Lee, Matthew Sernett (September 2018). Waterdeep: Dragon Heist. Edited by Jeremy Crawford. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 111. ISBN 978-0-7869-6625-7.

- ↑ Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford, Christopher Perkins (2014-09-30). Monster Manual 5th edition. Edited by Scott Fitzgerald Gray. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 221. ISBN 978-0786965614.

- ↑ Jeff Grubb, Kate Novak (October 1988). Azure Bonds. (TSR, Inc.), chap. 12, p. 137. ISBN 0-88038-612-6.

- ↑ Steven E. Schend (September 1996). Undermountain: Maddgoth's Castle. (TSR, Inc), p. 12. ISBN 0-7869-0423-2.

- ↑ Wolfgang Baur and Lester Smith (1994-07-01). “The Book of Chaos”. In Michele Carter ed. Planes of Chaos (TSR, Inc), p. 22. ISBN 1560768746.

- ↑ Erin M. Evans (December 2013). The Adversary. (Wizards of the Coast), chap. 14, p. 225. ISBN 0786963751.

- ↑ Ed Greenwood and Roger E. Moore (November 1984). “Treasure Trove”. In Kim Mohan ed. Dragon #91 (TSR, Inc.), p. 54.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Larian Studios (October 2020). Designed by Swen Vincke, et al. Baldur's Gate III. Larian Studios.

- ↑ slade (1996). How the Mighty Are Fallen. (TSR, Inc), p. 62. ISBN 0-7869-0537-9.

- ↑ Ellen Boener (February 2023). “Xenk and the Helmet of Disjunction”. In Jonathan Manning, Zac Boone eds. Honor Among Thieves: The Feast of the Moon (IDW Publishing), pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-1-68405-911-9.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Christopher Perkins, James Haeck, James Introcaso, Adam Lee, Matthew Sernett (September 2018). Waterdeep: Dragon Heist. Edited by Jeremy Crawford. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 36. ISBN 978-0-7869-6625-7.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, James Haeck, James Introcaso, Adam Lee, Matthew Sernett (September 2018). Waterdeep: Dragon Heist. Edited by Jeremy Crawford. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 212. ISBN 978-0-7869-6625-7.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, James Haeck, James Introcaso, Adam Lee, Matthew Sernett (September 2018). Waterdeep: Dragon Heist. Edited by Jeremy Crawford. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7869-6625-7.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, James Haeck, James Introcaso, Adam Lee, Matthew Sernett (September 2018). Waterdeep: Dragon Heist. Edited by Jeremy Crawford. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 62. ISBN 978-0-7869-6625-7.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins, James Haeck, James Introcaso, Adam Lee, Matthew Sernett (September 2018). Waterdeep: Dragon Heist. Edited by Jeremy Crawford. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7869-6625-7.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins (November 2018). Waterdeep: Dungeon of the Mad Mage. Edited by Jeremy Crawford. (Wizards of the Coast), pp. 13, 16, 21, 26, 31, 33. ISBN 978-0-7869-6626-4.

- ↑ Christopher Perkins (November 2018). Waterdeep: Dungeon of the Mad Mage. Edited by Jeremy Crawford. (Wizards of the Coast), p. 226. ISBN 978-0-7869-6626-4.

Connections[]

Ceremorphs

Brainstealer dragon • Gnome ceremorph • Gnome squidling • Illithiderro • Mindwitness • Mozgriken • Tzakandi • Uchuulon • Urophion • Yuan-tillithid

Related Creatures

Brain golem • Cranium rat • Nyraala golem • Illithidae • Illithocyte • Intellect devourer • Mind worm • Neothelid • Nerve swimmer • Oblex • Oortling • Ustilagor